26 into 1 won't go

Why are the unemployed being made scapegoats for failing employment policies? By Michael Taft.

Media outlets are reporting a new crackdown on the unemployed. Apparently, the Department of Social Protection intends to introduce new regulations whereby ‘target-dates’ for exiting the Live Register will be set for different categories of unemployed. If someone remains on the Live Register past that target-date, they may be subject to a new set of interviews and investigations which could lead to reductions in or even ending of their unemployment payment. This, no doubt, reflects the Minister’s description of unemployment as a ‘lifestyle’ choice for a growing number of jobless, especially young jobless.

This also reflects a new twist in victimising the unemployed for a crisis not of their making.

It is also reflects a policy mind-set that is detached from the reality of the labour market and even from the Government’s own employment projections.

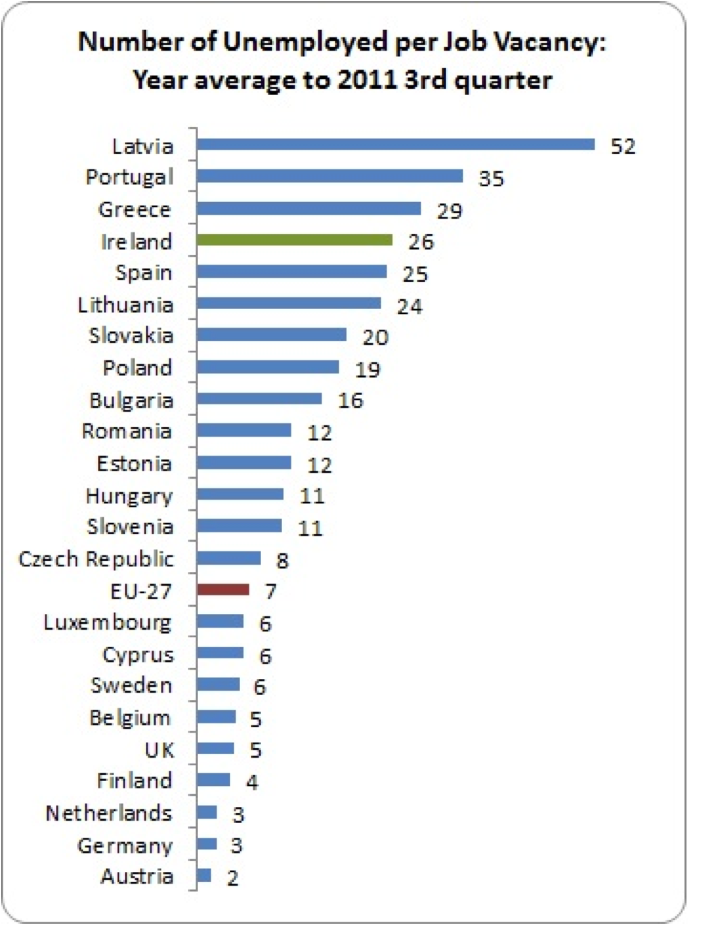

First, Eurostat produces a ‘job vacancy rate’ that measures the number of job vacancies in the EU economies. Using this we can estimate how the number of job vacancies compares with the actual number of unemployed. What is the ratio of unemployed per job vacancy in Ireland? 26:1. Let’s ‘reflect’ on that for a moment.

- There are 26 unemployed people for every 1 job vacancy.

How do we compare with other EU countries? The first chart shows the figures for the 23 EU countries whose data are available at Eurostat. The numbers are calculated from the Eurostat data using conservative assumptions that if anything are likely to result in an underestimate of the figures shown. Ireland is one of the worst performers in the EU. It ranks 4th last out of 23 countries reporting, with more than three times the EU-27 number of unemployed persons per vacancy. The figures for some countries require some qualification, but are mostly accurate enough to provide a reasonable picture across Europe.

However, the crucial point is that one can interview, examine and investigate the unemployed for as long as whenever – if there are 26 people chasing one vacancy, then the dole queues will continue to stretch out on to the street. To threaten reduction or suspension of unemployment payments in such conditions is little short of callous.

But this is all convenient for the Government because it takes attention away from the driving force behind unemployment – the simple lack of jobs. It also takes attention away from the Government’s losing battle over job creation – a battle they admit they’re losing:

- In April of last year the Government projected that there would be over 100,000 new net jobs in the economy by 2015.

- In the last budget they reduced this job creation projection to 62,000.

This explains why they revised their unemployment projections in 2015 from 10 % (in April 2011) to 11.6% in the last budget.

Indeed, the Government has admitted that there will be no short-term relief from unemployment. In the Regulatory Impact Analysis in the appendix of the Industrial Relations (Amendment) (No.3) Bill, 2011, the Government openly admits:

“Ireland has experienced a very sharp increase in unemployment in recent years, with little prospect of improvement in the short term…”

So with employment projections shrinking, unemployment projections rising, and a public admission that the jobless situation will not improve in the short-term, the Government thinks it’s a good idea to start targeting the unemployed, rather than the policies that would get them back to work.

No matter what is done using supply-side policies –through training, up-skilling or negative incentives – you cannot squeeze 310,000 unemployed into the approximately 13,000 total jobs that are available (calculated from the most recent Eurostat data, 3rd quarter 2011). Even if all the vacancies are filled instantly, approximately 300,000 will remain unemployed. Essentially, what training does in terms of unemployment in this situation is to change the names of the lucky ones to get jobs.

It has been also argued that the problem is a mismatch between the unemployed and the jobs available. These figures give the lie to that as the central problem. It is true that there are skill mismatches, notably due to the downsizing of the swollen construction sector in the boom. However, the large majority of these workers could be employed in other sectors with a certain amount of re-training - but only if the jobs are there. And herein lies the rub. There are few jobs, as the data above show. Punishing people will not solve the problem. Only the provision of jobs will.

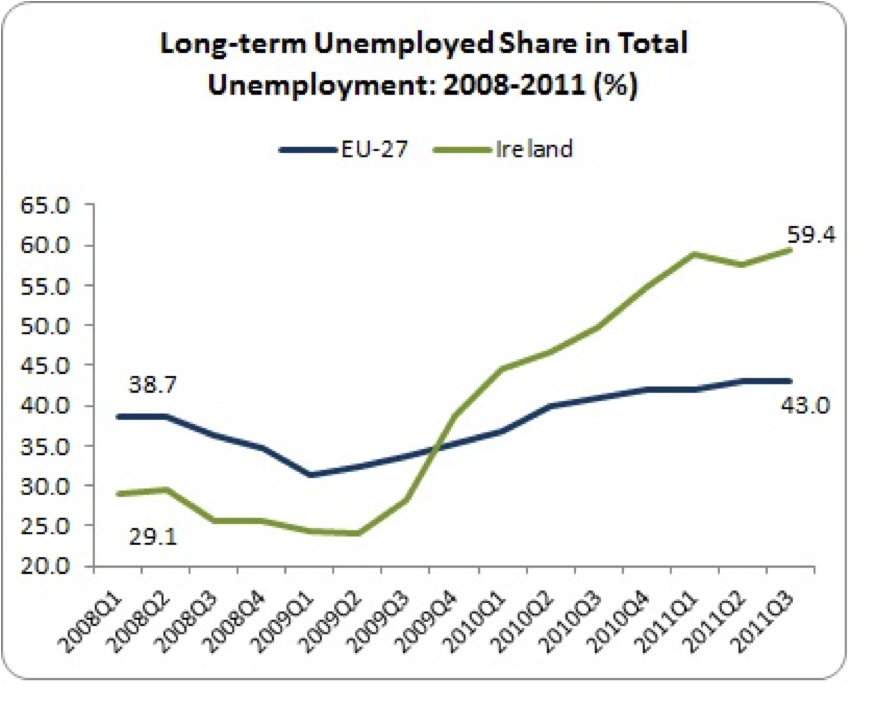

Ireland has 59.3% of the unemployed out of work for at least a year, over 180,000 people, and this number has increased sharply, well above that of the EU countries as a whole, as the second chart shows. The reason the unemployed are out of work is due to the lack of jobs, and not a sudden bout of laziness in the population. In the 27 countries of the EU, Ireland has the third highest long-term unemployment share among total unemployment, after Slovakia and Bulgaria, both of which had particular historical problems including the de-industrialisation that followed the shift from Communism.

By delaying the solution to this problem, permanent damage is done to the prospects of many unemployed, as many studies show, referring to a lasting ‘scarring’ effect. Youth unemployment is also particularly high in Ireland compared to other EU countries, coming 6th last in the ranking with a 30% unemployment rate among youth.

While measures to support the long-term unemployed will certainly be welcomed, Breda O’Brien from the Irish National Organisation of the Unemployed is sceptical:

“Breda O’Brien said the new service would assess people but that the supports offered to those with a higher probability of re-entering employment would be minimal. ‘The Government has to seriously address this issue. It cannot be threatening people to have their social welfare cut if there is no job there.’”

Reducing or cutting off unemployment pay becomes a matter of punishing the unemployed, something that was supposed to have gone out with the Poor Law of centuries past. Why is policy regressing to this approach of Victorian times? And why are the unemployed being made scapegoats for failing employment policies?

Supply-side policies of any kind – the only ones that are being tried – simply cannot work in this context. Only demand-side policies that actually create the required number of jobs can have an effect on unemployment of any significance. {jathumbnailoff}

I am grateful to Ronan O’Brien for his contribution to the data and analysis.

Image top: Workers' Party of Ireland.