The politics of counting and the myths of migration

Writing about statistics in the 1950s, Darrell Huff noted: "There is something fascinating about [them]. One gets such wholesale returns of conjecture out of such a trifling investment of fact." As it was, so it ever will be, as Mary Gilmartin finds.

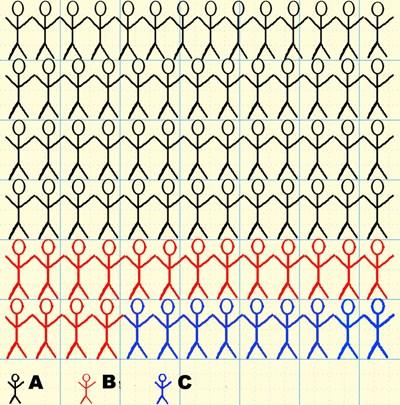

When it comes to migration, big numbers make headlines. It worked from the late 1990s onwards, with reports of Ireland being 'swamped' by 'floods' of asylum seekers. It worked in 2004, when travelling 'hordes' of pregnant women led to a rapid and dramatic change in the basis of Irish citizenship. And it still works today, as the ESRI fills our airwaves with predictions of 1980s-style mass emigration to come.Big numbers make headlines. It doesn't seem to matter that they rarely have any basis in fact. Take the 'floods' of asylum seekers, for example. Add up all the people who have claimed asylum in Ireland from 1992 to 2009 – a period of 18 years – and it comes to 83,068. That's an annual average of 4,615 asylum applications, the vast majority of which are unsuccessful.

How about the 'hordes' of pregnant women who forced us to change our citizenship rules? There were just 442 births in the Rotunda and Holles Street hospitals in 2003 to non-EU nationals who booked into the hospital late or had no booking – many of these women were legally resident in Ireland, and some were transferred from other hospitals because of complications.

And what of mass emigration? The ESRI's figures are a forecast, and their previous forecasts on migration have not been particularly accurate. In Spring 2009, for example, ESRI forecast net outward migration for the year to April 2009 of 30,000. According to the CSO, net outward migration for the year to April 2009 was 7,800: the ESRI's forecast was out by over 250 per cent. In Summer 2009, the ESRI forecast net outward migration of 40,000 in the year to April 2010. The CSO calculated this as 34,500. It was a much better forecast from the ESRI, but still an overestimate of net outward migration of 15 per cent.

Big numbers make headlines. Behind those big numbers are a series of facts that do not add up to the headline figures, and a collection of people whose lives are more complicated than the numbers suggest. In Ireland, big numbers that suggest mass involuntary emigration have a further, insidious implication. In times of crisis, migrants often become scapegoats, and there are signs that this is now happening in Ireland. Labour party TD Ruairi Quinn recently questioned "why we export nurses on the one hand and import Filipino nurses on the other", implying that Filipino nurses are directly responsible for the public sector recruitment ban.

The fact is that we have a poor record on gathering statistics on migration in Ireland. There is no formal record of either entry or departure for migrants from the EU, who make up two thirds of those with nationalities other than Irish. There is no formal record of Irish nationals who migrate from Ireland, so it is only the fact-gathering of other states – the UK and Australia, for example – that allows us to see where Irish migrants are going. The CSO does a good job with limited resources, but is forced to rely on the Quarterly National Household Survey for its population figures. There is one exception. Asylum seekers in Ireland – the most vulnerable group of migrants – are carefully counted and recorded.

In this absence of accurate statistics on migration, myth thrives. Whether it's the 'immigrant exodus' from Ireland, or the beleaguered Irish once again flooding the shores of Britain, migration myth strikes an emotive chord, easily exploited for political or economic purposes. What myth doesn't do is help us understand who is leaving or staying in Ireland, and why. Nor does it help us understand the new forms of migration – such as circular migration between Ireland and other EU countries – that are emerging in the face of this crisis.

[Image by Eadaoin O'Sullivan]